Corrected 2008.04.17: Restored missing photos. Other edits.

Updated 2008.04.16: In response to Manhattan Users Guide, provided additional explanation of why I put up a bat house: to help prevent their extinction.

Updated 2008.04.15: Added inline links, plus link to BatCatalog, BCI’s online store.

Today I installed my first bat house, on the side of my tree fort, the second floor porch on the back of our house. It’s a two-chambered house which I purchased online three weeks ago from BatCatalog, the online store of Bat Conservation International (BCI). (Disclosure: I’m a supporting member of BCI.)

BCI has free plans for a single-chambered house [PDF] on their Web site, and they have a handbook of many different plans for folks to design and build their own houses. I chose a pre-built house, for my first one. Because it’s my first, I wanted one that was well-designed and built. I also wanted to get one installed in time, possibly, for this year’s summer breeding season. I’m handy, but I procrastinate; if I started building a house now, I’d be lucky if I got it done for NEXT year.

Contents

Why build (or buy) and install a bat house?

I know some of you are thinking, “WHY?!”

Why build a bat house? The simple answer is because having bats in the area is an easy way to observe nature at her finest, and the bats will provide a guaranteed show every warm evening of the summer season. Bats are insect eating-machines that may help keep troublesome insect populations in check. In addition, providing bat houses is one method of encouraging bats to relocate their colonies out of buildings.

– Bats Wanted, Conservationist, February 2008, NYS DEC

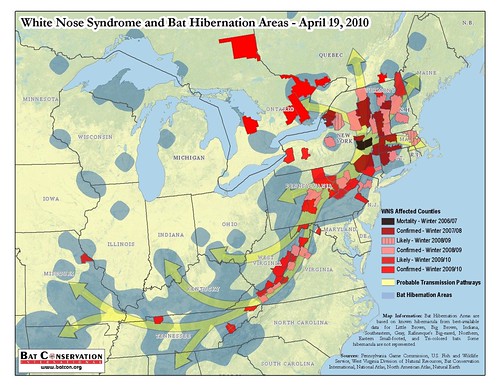

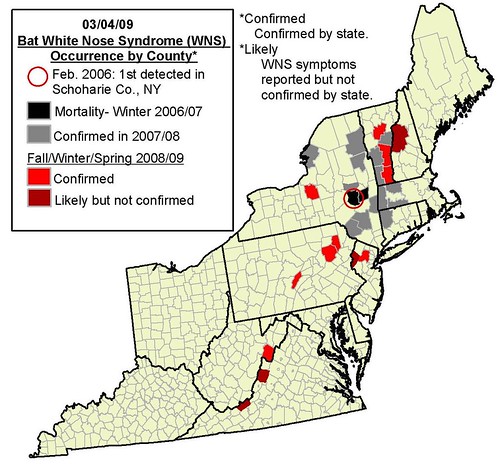

This year, there is an additional, more urgent, reason. I wrote a few weeks ago about the disease that is wiping out bats hibernating in their Winter colonies across the northeast. The disease has been confirmed in four states so far: New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Mortality has been estimated to be as high as 90% in some of their hibernation caves. If the cause cannot be discovered and eliminated, we may lose entire species of bats in just a few years.

Bats are not prolific breeders. A mating pair may have a single pup a season. Even if scientists find a cause for the disease, and can prevent further mortality, it will take decades for bats to recover the numbers they’ve lost in a single season.

Artificial roosts, such as my new bat house, are bats’ “summer homes” and, more important, their nurseries: they use these to bear and raise their young. It’s my hope that by creating more summer roosting and nursery sites, we can increase their health and rates of survival during the year. They need all the help we can give them.

Where can bat houses be used?

Where will bat houses be effective? And where should they be placed? The answer, if familiar, is location, location, and location:

- It should be located near fresh water, no more than 1/2 mile away. Houses within 1/4 mile have higher rates of occupancy.

- The house must be mounted at least 12 feet high, either on a free-standing pole or the side of a building.

- Away from bright lights.

- They must be away from tree limbs and other aerial barriers such as wires which can create obstacles to finding the bat house or provide launches for predators.

In an urban area, it’s a challenge to find these conditions. I live just over a half-mile, as the bat flies, from Prospect Lake in Prospect Park, the largest body of fresh water around. But my area is more suburban than urban, with large lots and open yards. Many of my neighbors have “water features” in their gardens: ponds or pools which can serve as alternate sources of fresh water.

The bat house in place

I think I have a good place for my bat house: on the side of my tree fort, facing south-southeast. The garden beds below are in full sun all summer. Even in Winter, when the sun is low and the beds are shaded by our neighbor’s house, the bat house is mounted high enough to receive full sun. My neighbor has a security light, but the house is placed behind its main field of illumination, out of direct line of the light itself.

Most nursery colonies of bats choose roosts within 1/4 mile of water, preferably a stream, river or lake. Greatest bat-house success has been achieved in areas of diverse habitat, especially where there is a mixture of varied agricultural use and natural vegetation. Bat houses are most likely to succeed in regions where bats are already attempting to live in buildings.

– Criteria for Successful Bat Houses [PDF], BCI

Bat houses should be mounted on buildings or poles. Houses mounted on trees or metal siding are seldom used. Wood, brick or stone buildings with proper solar exposure are excellent choices, and houses mounted under eaves are often successful. Single-chamber houses work best when mounted on buildings. Mounting two bat houses back-to-back on poles (with one facing north and the other south) is ideal. Place houses 3/4-inch apart and cover both with a galvanized metal roof to protect the center roosting space from rain. All bat houses should be mounted at least 12 feet above ground, and 15 to 20 feet is better. Bat houses should not be lit by bright lights.

– Criteria for Successful Bat Houses [PDF], BCI

Houses mounted on the sides of buildings or on metal poles provide the best protection from predators. Metal predator guards may be helpful, especially on wooden poles. Bats may find bat houses more quickly if they are located along forest or water edges where bats tend to fly. However, they should be placed at least 20 to 25 feet from the nearest tree branches, wires or other potential perches for aerial predators.

– Criteria for Successful Bat Houses [PDF], BCI

Where you mount your bat house plays a major role in the internal temperature. Houses can be mounted on such structures as poles, sides of buildings and tall trees without obstructions. Houses placed on poles and structures tend to become occupied quicker than houses placed on trees. Bat houses should face south to southeast to take advantage of the morning sun. In northern states and Canada, bat houses need to receive at least 6 to 8 hours of direct sunlight. It is also advantageous to paint the house black to absorb plenty of heat (when baby bats are born, they need it very warm). Use non-toxic, latex paint to paint your bat house and only paint the outside. Your bat house should be mounted at least 15 feet above the ground, the higher the house the greater the chance of attracting bats.

– Where to put up a bat house in the Northeastern United States, Organization for Bat Conservation

Bat houses installed on buildings or poles are easier for bats to locate, have greater occupancy rates and are occupied two and a half times faster than those mounted on trees.

– Attracting Bats [PDF], BCI

What makes a well-designed bat house?

The bat house before installation

Successful bat houses are much larger than one might think. Take a look at the photo above. The house is leaning against a table of standard height. That’s a garden spade next to the bat house for scale.

Bats are communal creatures. Because they’re so small, they need each other to keep warm at night. The more bats, the better. The larger the bat house, the better. This is especially important for infant survival in nursery colonies. My relatively small two-chambered bat house can shelter up to 100-150 bats.

The spacing of the chambers is important. Just large enough that the bats can crawl up inside, small enough to reduce the attractiveness to potential problem nest-builders like wasps and hornets.

The bottom of the bat house is open. Guano will fall down to the ground below. It doesn’t collect in the bat house, so it doesn’t need to get cleaned out.

The key to a successful bat house in the northeast’s cooler climate is to keep the house hot. Be sure to seal the upper portions so that warm air cannot escape, paint the house a dark color, and place it in the sunniest location you have that is near cover and not far from water. Maintenance, such as repairing a warping exterior that no longer traps warm air, will be an issue over time, so consider providing some kind of protective cover.

– Bats Wanted, Conservationist, February 2008, NYS DEC

Only in the most extreme southwest should bat houses be painted a light color. In my area, a dark brown would also work with a bat house placed in ideal conditions. Because my bat house is backed by an open porch, and not the house itself, I chose the darkest color, a flat black, to compensate for the lack of insulation one would get from mounting on the side of a house.

When should bat houses be installed?

According to DEC’s Conservationist magazine, in New York State, bat houses are most likely to attract either little brown or big brown bats. So, where do you get the bats?

Bats have to find new roosts on their own. Existing evidence strongly suggests that lures or attractants (including bat guano) will NOT attract bats to a bat house. Bats investigate new roosting opportunities while foraging at night, and they are expert at detecting crevices, cracks, nooks and crannies that offer shelter from the elements and predators.

– Attracting Bats [PDF], BCI

Bat houses can be installed at any time. However, it may take up to two years for bats to “adopt” a shelter. The best time to install a new bat house is in late Winter/early Spring, before bats emerge from winter hibernation and begin seeking summer nursery sites. I saw a bat flying at dusk at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden last Thursday, during our botany class walkaround. Now may be too late for my bat house for this year. We’ll see what happens.

Bats return from migration and awaken from hibernation as early as March in most of the U.S., but stay active year-round in the extreme southern U.S. They will be abundant through out the summer and into late fall. Most houses used by bats are occupied in the first 1 to 6 months (during the first summer the bat house was erected). If bats do not roost in your house by the end of the second summer, move the house to another location.

– Where to put up a bat house in the Northeastern United States, Organization for Bat Conservation

[bit.ly]

Related Content

Northeastern Bats in Peril, March 18, 2008

Other posts about bats and White-Nose Syndrome

Links

Bats Wanted, Conservationist, February 2008, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

Bat Conservation International (BCI)

BatCatalog, BCI’s online store

The importance of bat houses, Organization for Bat Conservation

The Bat House Forum

Wikipedia: Bats