Updated 2013-09-05: CORRECTION – The white-flowering plant is Eupatorium hyssopifolium, Hyssop-leaf Throughwort, not E. perfoliatum, Common Boneset, as I misidentified it.

At a glance – say, highway speed – this may appear to be yet another old-field meadow, biding its time before it transitions into shrubland and eventually forest. This is Hempstead Plains, one of several mature grasslands on Long Island, and the only true prairie east of the Appalachian Mountains.

Hempstead Plains on the grounds of Nassau Community College in East Garden City, Nassau County, NY. The white-flowering plants are Eupatorium hyssopifolium, Hyssop-leaf Throughwort.

On Sunday, August 25, I joined three other native plant lovers for a whirlwind tour of Hempstead Plains. We had only an hour; I could have spent several hours there. For me, this was a pilgrimage. I spent most of my childhood on Long Island.

Our guide was Betsy Gulotta, Conservation Project Manager of the Friends of Hempstead Plains, Department of Biology, Nassau Community College, on whose grounds this remnant stands. Here Betsy points out Apocynum cannabinum, Indian Hemp, at the start of our visit.

A Brief Natural History of Hempstead Plains

New York’s Long Island comprises four counties; from east to West they are Suffolk, Nassau, Queens, and Kings (aka Brooklyn). If you look down from space, and maybe squint a bit, Long Island resembles a fish: Brooklyn is the face, Queens is the head and gills, and Nassau and Suffolk are the body and tail.

The fish shape of Long Island arises from two ridges, running roughly east-west. The ridges stand out as light yellow to white in this Digital Elevation Model (DEM) map of Long Island. I’ve highlighted the location of Hempstead Plains in Nassau County, right about where the fish’s pectoral fins would be. Map: Dr. J. Bret Pennington, Department of Geology, Hofstra University

Map: Dr. J. Bret Pennington, Department of Geology, Hofstra University

These ridges are terminal moraines: deposits of sand, gravel and rock left behind as the Wisconsin glaciation made its last stand, then retreated, 20,000-19,000 years ago. Long Island is part of the Outer Lands, the archipelago formed by these moraines, that extends to Cape Cod.

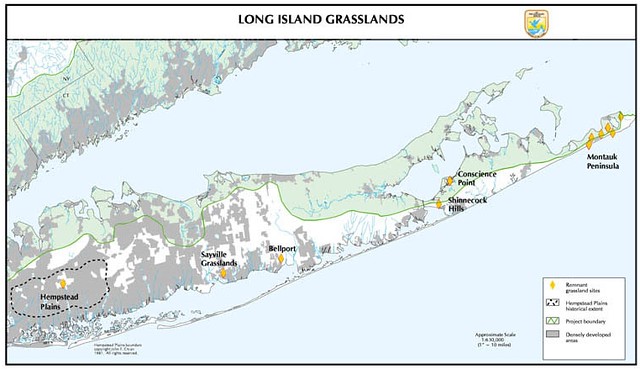

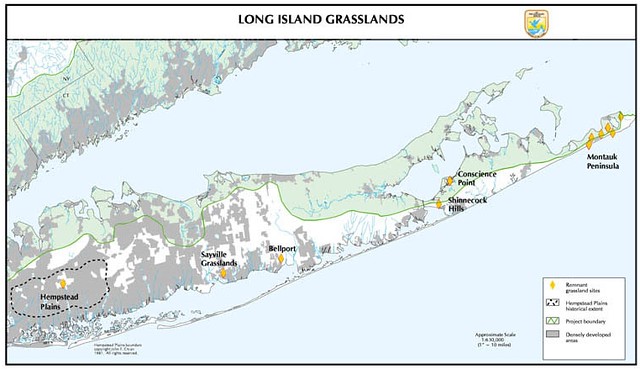

South of the moraines are outwash plains, laced with streams and rivers leading to the bays of Long Island’s southern shores. Hempstead Plains once spanned the westernmost extent of these plains, bounded on the west and north by the northern Harbor Hills Moraine, and on the east by the Ronkonkoma Moraine, where it abuts the Harbor Hills Moraine. This map, from a U.S Fish & Wildlife Service survey of grasslands habitats on Long Island, shows the estimated original extent of Hempstead Plains prior to European colonization, based on soil surveys and historical accounts.

Why Hempstead Plains is Special

Even if no more of this land were taken up in farms, the continued growth of New York City is bound to cover it all with houses sooner or later, and it behooves scientists to make an exhaustive study of the region before the opportunity is gone forever.

– The Hempstead Plains: A Natural Prairie on Long Island, Roland M. Harper, 1911

The existence and persistence of this prairie has yet to be completely explained.

There’s evidence of periodic fire disturbance, whether natural or man-made, even prior to European colonization. (Today, they mow to keep invasive species in check.) But the pine barrens that once extended east of here are also adapted to fire. Why prairie, not pine barrens, here?

The soil here is nothing like the deep topsoils of midwestern prairies. Most of Long Island is a glacial deposit of sand and gravel. Perhaps that balances out the relatively high rainfall we get here. Then why wasn’t there more prairie on Long Island?

Hempstead Plains shares another characteristic with arid and semi-arid lands, including prairie: biological soil crust. During our visit, there were a few places where the lichen soil crust was visible. Where it’s disturbed, as in this photo, you can see the sandy, gravelly underlying soil.

With such an unusual confluence of conditions, Hempstead Plains is home to several species that are locally or globally rare and threatened. During our visit, we were privileged to see Agalinis acuta, Sandplain Gerardia, in bud.

Back to our little troupe; here we are closely examining a specimen of Baptisia tinctoria, Blue Indigo. We remarked on how different the Hempstead Plains Baptisia looks from horticultural varieties, even of the same species.

Wild areas such as Hempstead Plains provide critical reservoirs of seeds for conservation and restoration efforts. Local ecotypes of native plants are adapted to local conditions. They’ve co-evolved with other organisms in their environment, and support more wildlife than cultivars. Their populations exhibit diversity that disappears when we select and propagate plants for our purposes, such as “garden value.”

Local ecotypes are rarely available commercially. For example: several of the plants offered at June’s Long Island Native Plant Initiative Plant Sale were propagated by the Greenbelt Native Plant Center from seed collected at Hempstead Plains. Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s elimination of field work threatens such regional conservation efforts.

The Hempstead Plains is the last remnant of native prairie grassland that once covered 40,000 acres of central Nassau County. Today, as a result of commercial development only a few acres remain. The site is considered highly ecologically and historically significant. The Hempstead Plains supports populations of federally endangered and globally rare plants among its 250 different kinds of vegetation as well as several plant species that are now considered rare in New York State. It represents one of the most rapidly vanishing habitats in the world, along with scores of birds, butterflies, and other animals that are vanishing with it.

– About the Plains, Friends of Hempstead Plains

Plants

Here are some of the plants we met during our visit. First, some characteristic tall-grass prairie species.

Andropogon gerardii, Big Bluestem

Panicum virgatum, Switchgrass

Sorghastrum nutans, Indian Grass

And a handful of other, smaller grasses. There are 35-40 species of grasses, native and non-native, at Hempstead Plains.

Dichanthelium clandestinum, Deer-Tongue Grass (in the center of the weeds)

Eragrostic spectabilis, Purple Lovegrass

Schizachyrium scoparium, Little Bluestem

Here are some more conventional “wildflowers.”

Eupatorium hyssopifolium, Hyssop-leaf Throughwort

Euthamia caroliniana/, Slender Goldentop, Flat-top Goldenrod

Visiting Hempstead Plains

The site is not open to the public except for scheduled guided tours. Plants aren’t labelled – it’s a wild area, not a botanic garden – so you’ll want a knowledgable guide, anyway! Check the Activities page on the Friends of Hempstead Plains web site for their calendar. They have regularly scheduled tours on Friday afternoons, and volunteer days on Saturday mornings, into November.

Getting there is confusing. It’s really easy to miss the turnoff. I circled the entire campus of Nassau Community College before I was able to get back on approach to Perimeter Road, where the parking area is located. I could have used a navigator.

They’re working on a new Interpretive Center, scheduled to be open in 2014. The building site is a corner of the property that was already less than pristine. Nevertheless, they’re disturbing the soil as little as possible. The composting toilet will be an above-ground model, instead of one that requires excavation. The building will have a green roof populated with plants propagated from the site.

I look forward to a return visit.

Related Content

Flickr photo set from my visit

Long Island Native Plant Initiative Plant Sale 2013

All my Native Plants blog posts

My Native Plants page

Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Slash and Burn “Campaign for the 21st Century”, 2013-08-23

Links

Friends of Hempstead Plains

Hempstead Plains Grassland, New York Natural Heritage Program

Wikipedia: Hempstead Plains

Saving Bits of Nassau’s Original Prairie, Barbara Delatiner, New York Times, 2003-06-22

An urban nature reserve takes shape on the Diana Center’s green roof (Video), Hilary Callahan, Barnard College News, 2011-08-10 (This Project uses plants propagated by the Greenbelt Native Plant Center from Hempstead Plains seed stock)

Long Island Native Grass Initiative, Nassau County Soil & Water Conservation District

Coastal Grasslands (PDF), Long Island Sound Habitat Restoration Initiative, February 2003

Long Island Grasslands, Significant Habitats and Habitat Complexes of the New York Bight Watershed, 1996-1997, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Long Island Botanical Society

Long Island Native Plant Initiative

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) Maps of Long Island, Dr. J. Bret Pennington, Department of Geology, Hofstra University

Geology of Long Island, Garvies Point Museum and Preserve

An Introduction to Biological Soil Crusts, SoilCrust.org

Historical References:

The Vegetation History of Hempstead Plains (PDF), Richard Stalter and Wayne Seyfert, St. John’s University, Proceedings of the 11th North American Prairie Conference, 1989 (Hosted at the Digital Commons, University of Nebraska, Lincoln)

The Hempstead Plains: A Natural Prairie on Long Island, Roland M. Harper, Bulletin of the American Geographical Society , Vol. 43, No. 5 (1911), pp. 351-360 (An edited version was republished in Torreya, Volume 12, 1912)

Soil Survey of the Long Island area of New York (PDF), by Jay A. Bonsteel and Party, Field Operations of the Bureau of Soils, 1903 (Hosted at New York Online Soil Survey Manuscripts, Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA)