Observing the diversity of life that coexists in one place is one of the rewards of visiting the same natural area over a long period of time. My garden not only offers myself and passersby such an observatory. It’s also a laboratory in which I can research how insects engage with their environment – both biotic and abiotic – and imagine, design, and create habitat to better provide for their needs.

I use iNaturalist to document the diversity of life in my garden. Although I only posted my first iNaturalist Observation in 2017, my garden Observations now span more than a decade. As of this year, I’ve documented over 400 insect species making use of my garden.

This biodiversity, and my documentation of it, is intentional. And although all of this is by design, all I can do is uncover the latent urban biodiversity in and around my garden. Each new species I find is a surprise to me.

Native Plants

As I explained in last year’s Home of the Wild, native plants have been a significant focus of my gardening since we bought our home and I started the current garden in 2005. I’m always researching and experimenting with new species. And, like any avid gardener, I’m always killing things off, too.

I do my best to track my acquisitions, and failed plantings, in a spreadsheet. I categorize the species by whether they are native to the five counties of New York City, native to the NYC region – e.g.: within two counties – or are some other species native to eastern North America.

This chart summarizes the increase in native plant diversity in my garden over the years. Stacked columns, plotted against the left axis, show the number of species I acquired each year: blue for NYC-native, red for NYC-regional, and green for eastern U.S. native plant species. The large undated bar on the left represents plants I brought with me from prior gardens, or for which I’ve lost track of when or how I got them. The lines, ploted against the right axis, show the total number of species: blue for NYC-native plant species, and green for everything else.

2014 stands out as an exceptional year for plant acquisitions. That was my first year visiting the Native Plants in the Landscape Conference in Millserville, Pennsylvania. It has an enormous accompanying native plant sale with vendors from all over the mid-Atlantic, of which I took full advantage.

I maintain a Wish List of plants I want to try to grow in my garden. (Anyone know of a NYC-regional source for dwarf prairie willow, Salix occidentalis?!) The past few years I have targeted species for their ecological value in my garden:

- Fill in plant families that are missing, or under-represented, in my garden, such as Apiaceae, e.g.: Zizia aurea.

- Extend the flowering season, especially early in the year when native plant blooms are scarce. For example: Packera is the earliest-blooming Asteraceae I’ve found, so I’m trying to establish that in my garden.

- Grow more plants to support specialist flower visitors, such as bees.

As of this year, I’m growing nearly 300 species of native plants, over 200 of which are native to New York City. With that increase in plant diversity, there’s been an increase in insect diversity (though habitat needs more than having the right plants).

Insect Species

Most of the insects that have visited my garden over the past decade fall into one of six groups:

- Diptera, flies: 103 species

- Wasps. i.e.: other Hymenoptera, excluding bees and ants: 70 species

- Coleoptera, beetles: 57 species

- Epifamily Anthophila, bees: 55 species

- Lepidoptera, butterflies, moths, and skippers: 55 species

- Hemiptera, bugs: 43 species

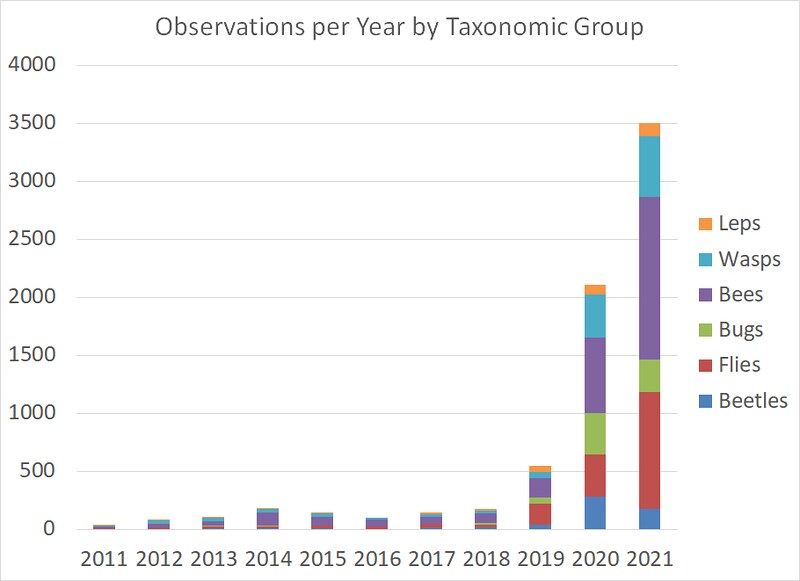

That’s where things stand today. But this didn’t happen all at once. This chart shows how I’ve accumulated species records in my garden for each of these groups over time. We can see that the slope of the lines increased sharply over the past three years, from 2019 through 2021.

It’s a little easier to see which taxa contributed most to the increases if we look instead at just the new species, instead of the total number of species. This stacked column chart shows the number of new species I’ve found each year in my garden, for each of my six focus taxa. Again, the last three years stand out as being responsible for most of the increase.

The color codes of the stacked column segments are the same as the lines in the previous chart to make it easier to draw comparisons between the two:

- I’ve seen most of the fly species in just the past two years.

- It’s the same for the wasp species.

- Beetles saw a spike in new species observed in 2017 and again in 2020. Otherwise, a fairly steady uncovering of new species each year.

- Bees have seen a remarkably steady discovery of new species over the years. The first few years found lots of new species. More recent years not so much.

- Butterflies, moths, and skippers have also shown up mostly over the past three years.

- Most of the bug species were found during the three year span from 2018-2020. Not so much this past year.

I believe that at least some of these increases reflect success in creating habitat for diverse insect species. But my observing behaviors have not been consistent over the years. Am I seeing more species just because I’m spending more time looking for them? And — if so — how much observation do I need to do to be confident I’m adequately sampling my garden?

Insect Observations

I ramped up my Observations the past two years – 2020 & 2021 – to increase my contributions to two iNaturalist Projects:

- Home Projects Umbrella, a collection of iNat “Home Projects” from aronud the world.

- The Empire State Native Pollinator Survey (ESNPS), and its Collection Project.

As mentioned above, I wrote about the first Project, and the history of my garden as insect habitat on my blog last year. ESNPS was originally scheduled to run only three years, from 2018 through 2020. Of course, the pandemic changed those plans; they decided to extend the iNaturalist portion another year, into 2021.

By concentrating on these two efforts, I increased my Observations in my own garden by a factor of 8. This year, I also invested in better macro equipment. So I was spending a lot more time in my garden, and was able to capture many more individuals with photographs good enough for identification.

The Empire State Native Pollinator Survey includes bees and Syrphidae, flower and hover flies, among its focal taxa. Although my increased observation found more of everything, bees and flies took up a greater proportion of the total observations.

How many observations do I need to make to have high confidence I have found most of the species present in my garden? This chart compares the number of species observed against the number of observations for the four most diverse taxa: flies, wasps, bees, and beetles. I’ve added labels for the two most recent years, to highlight that not only did they have the most observations, they are also the years I found the most species.

Last year was not a pace of observation I can sustain indefinitely. There’s a lot of effort in taking high-quality, identifiable macro photographs of insects in the garden to uploading them as verifiable observatinos in iNaturalist. Some days it took most of my waking hours, spread over multiple days, just to process all the photographs from a single day of observation.

My iNaturalist activity the past year was artificial, driven by the gamification offered by the two Projects in which I was actively “competing”. But this past year gave me a strong foundation for continuing to make effective observations. I look forward to being surprised by future discoveries in my garden.

Related Content

Hot Sheets Habitat, 2021-11-19

Documenting Insect-Plant Interactions, 2021-10-29

Home of the Wild, 2020-05-13