Tag Archives: February

Charismatic Mesofauna

Over the weekend I was inspired to write a little tweet storm. I thought it would make a good blog post.

It started with a blog post by entomologist Eric Eaton, who goes by @BugEric on his blog, Twitter and other social media. Benjamin Vogt, a native plants evangelist (my word, bestowed with respect) tweeted a link, which is how it came to my attention.

The Monarch is the Giant Panda of invertebrates. It has a lobby built of organizations that stand to lose money unless they can manufacture repeated crises. Well-intentioned as they are, they are siphoning funding away from efforts to conserve other invertebrate species that are at far greater risk. The Monarch is not going extinct.

– Bug Eric: Stop Saying the Monarch is a “Gateway Species” for an Appreciation of Other Insects

I grow milkweed in my garden – at least 3 different species. (I’m waiting to see if the other 3 species persist and return.) I’ve documented monarch butterflies visiting the past 2 years. Last year I got eggs, and caterpillars.

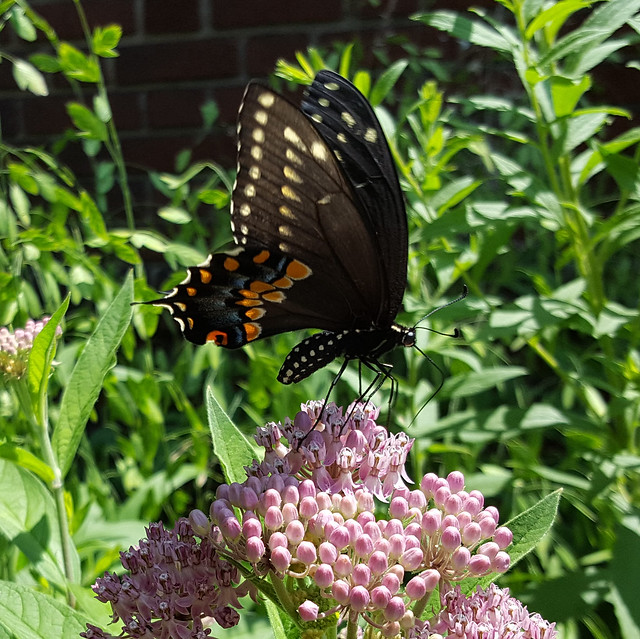

But monarchs aren’t the only visitors to my milkweeds.

A popular argument for making the Monarch an invertebrate icon is that “being such an icon has really helped us reach the average person about habitat and native plants and conservation, and by extension, the environment and climate change,” as one friend on social media put it. Well, if only that were true. If people who care about the Monarch had any understanding of ecology at all, they would not be complaining that “there are beetles eating the milkweed I planted for Monarchs!” They would not be devastated because one wasp killed one of the caterpillars.

As Eric noted in his article, gardeners who fret over “what’s eating my milkweed” are valuing their monarchs over the other invertebrates. Like these aphids.

Like the monarchs, their bright orange color is aposematic, warning potential predators of their milkweed-borrowed toxicity. No matter … They sustain other visitors, like this brown lacewing larva.

Or this Ocyptamus fuscipennis, syrphid/flower fly, showing great interest in the aphids on Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed, in my front yard.

And who knows what this Hymenoptera was hunting for.

And there are other floral visitors besides the charismatic butterflies.

There are many more I’ve yet to identify. All this on just three species of plants in my garden. Plants that some would grow only for the monarchs.

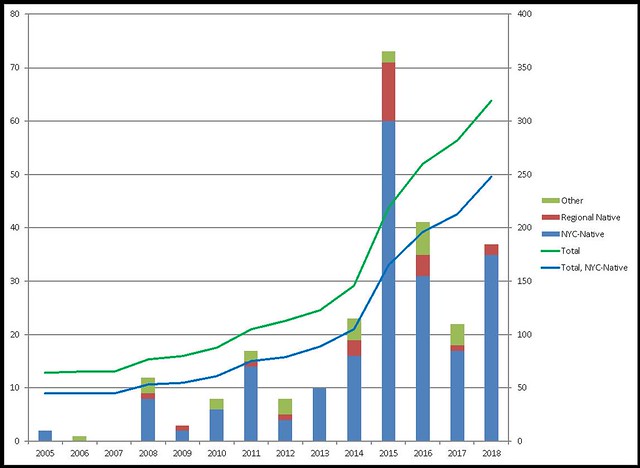

I’m growing over 200 species of plants native to New York City, and another 80 or so regional natives.

With all that botanical diversity has come insect diversity:

- 31 species of bees.

- 28 species of wasps.

- 23 species of flies.

- 20 species of beetles.

And, oh yeah, 24 species of butterflies, moths, and skippers. Including the charismatic monarchs.

| Family | Common Name | # Species |

| Coleoptera | Beetles | 20 |

| Diptera | Flies | 23 |

| Hemiptera | Bugs | 9 |

| Hymenoptera | Bees | 31 |

| Hymenoptera | Wasps | 28 |

| Lepidoptera | Butterflies, Moths, and Skippers | 24 |

Let’s plant milkweed, just not only for the monarchs.

And not just milkweeds.

Oh, and no pesticides.

Thank you.

Related Content

Blog Posts

Flickr photo sets

Danaus plexippus, monarch butterfly

Milkweed species I’m growing in my garden. (Not all the photos are taken from my garden.)

Links

Bug Eric: Stop Saying the Monarch is a “Gateway Species” for an Appreciation of Other Insects

Recipe: Crisp and Chewy Chocolate Chip Cookies

These cookies have been taste-tested recently at a going-away party and after-church coffee hour. Adults rave about this cookie. You will have no leftovers, even from a double batch.

I’ve been working on this recipe for a while, and I think I’ve finally got it to where I want it.

I started with “The Essential Chewy Chocolate Chip Cookie” from the King Arthur Flour Cookie Companion cookbook. I doubled the recipe, and made a few substitutions and additions, noted below.

I was getting the taste I wanted, but not the texture: they kept coming out too high and dry. They would rise in the oven, but they wouldn’t fall.

I finally realized I just needed to reduce the flour called for in the original recipe to balance my other changes. This made them come out perfect, just the way I wanted them: slightly browned and crisp at the edges, soft and chewy in the centers.

I also like to amp up the chocolate chips, both by increasing the amount, and using different kinds, mixing milk and semi-sweet chocolates. My favorite are the chocolate drops from NYC’s own Lilac Chocolates. They make them in at least three different varieties: milk, dark, and 72% extra-dark.

Pre-heat

Pre-heat your oven to 375F. You can also line some heavy-duty cookie sheets with parchment paper.

Ingredients

- 3 sticks (1-1/2 cups, 12 oz) butter, warmed to room temperature

- Optional: 1/2 C smooth peanut butter (husband John loves peanut butter in everything)

Whip up the butter until light and fluffy. Then cream the sugars into them and whip them up even more. The batter should be light brown in color.

- 1-1/3 C (10-1/2 oz) dark brown sugar

- 1-1/3 C (9-1/2 oz) granulated sugar

- 3/8 C (6T, 3-3/4 oz) maple syrup, as dark as you can get (this is a substitution for the corn syrup called for in the original recipe, and a 50% increase over the original amount)

Beat in the rest of the flavorings. If you’re using cider vinegar, it does double duty: first as the chemical reagent for the baking soda, second with the slight cidery taste.

- 2T (1/8C) cider vinegar (you can use white vinegar if you don’t have cider)

- 1/4 C (4T) vanilla extract (this is double the original recipe. I love vanilla!)

- 1 teaspoon espresso powder OR 1 Starbucks Via packet (I like Via because it has a longer shelf life than the usual plastic container of espresso powder, which ossifies into useless slag, and because they have a decaf italian/dark roast.)

- Optional: 1/2 teaspoon kosher salt (omit to reduce sodium)

At this point I’ll do a taste test, before beating in the eggs one at a time.

- 4 large eggs

You want to blend the baking soda and powder into the wet batter so they can dissolve, disperse, and begin their chemical reactions to give lift to the dough in the oven. I’ve made the mistake of sifting them with the flour, treating them as just other “dry” ingredients, and they don’t get incorporated as well.

- 1 teaspoon baking soda (this will react with the vinegar and brown sugar)

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

Sift and gradually/slowly stir in the flour, until no dry flecks or lumps remain. Again, I’ve made the mistake of treating the flour like the rest of the batter, trying to beat it in. That makes for tough, not tender, cookies.

- 4 C (16 oz) whole wheat flour flour, sifted (The whole wheat makes a big difference in the flavor and texture. The original recipe calls for all-purpose/white flour. This is a reduction by about 1/8 from the original amount.)

The dough will be wet. You should be able to scoop some out with a tablespoon, and have it stick to the spoon. If it’s too loose, add some more flour to get the texture you want.

Finally, stir in, by hand, the chocolate chips and chunks of your choice.

- 6 cups (36 oz) chocolate chips and/or chunks

Baking

- Pre-heat the oven to 375F. (But you did that already.)

- Cover a heavy-duty cookie sheet with parchment paper.

- Scoop out heaping tablespoons of dough onto the paper. Stagger them so they have room to spread without touching. On a standard-“half-sheet”, I can get 5 rows from one end to the other with 3 heaps at each end and the center, and 2 heaps in between those rows. 3, 2, 3, 2, and 3: a baker’s dozen!

- In the first few minutes after putting the tray in the oven, the dough should spread with the heat, and rise with the leaveners.

- Bake for 10-12 minutes. Your eyes and nose are the best judge of “done” here. Sniff for the slight smell of burnt sugar, and look for the edges to be set and just starting to darken. The centers should still look wet. Ideally, they will have started to collapse, but don’t wait for that – you don’t want them to set while risen.

- Remove the sheet and set aside. Let the cookies cool on the sheet until they slide easily without squishing, bending, or breaking up.

- Remove the individual cookies to a rack to cool completely. (Or eat while still warm and gooey).

Related Content

Links

Invasive Plant Profile: Chelidonium majus, Celandine, Greater Celandine

Revised 2015-02-23: This was one of my earliest blog posts, first published in June 2006. I’ve overhauled it to 1) meet my current technical standards, and 2) improve the content based on the latest available information.

Chelidonium majus, Celandine or Greater Celandine, is a biennial (blooming the second year) herbaceous plant in the Papaveraceae, the Poppy family. It is native to Eurasia. It’s the only species in the genus.

It’s invasive outside its native range, and widespread across eastern North America. It emerges early in the Spring, before our native wildflowers emerge, and grows quickly to about 2 feet. That’s one of the clues to identification. It’s also one of the reasons why it’s so disruptive. The rapid early growth crowds and shades out native Spring ephemerals.

Greater celandine is one of the first weeds I identified when we bought our home in 2005 and I started the current gardens. Here’s my collection of photos from the garden’s second year, in 2006, highlighting the characteristics that help to identify this plant. The photos (click for embiggerization) show:

- Full view of plants, showing growth habit, bloom, and ripening seedpods on the same plants. The plants in this picture are about two feet tall. In the middle and lower left of the picture, you can see the leaves of Hemerocallis (Daylilies) just peeking out from under the Chelidonium.

- Broken stem with orange sap. You can also see a small flower bud in the leaf axil to the left.

- Detail of flower. Notice the 4 petals, clustered stamens, and central pistil with white stigma.

- Detail of ripening seedpod. These seedpods are what made me think at first that this plant was in the Brassicaceae (or, if you’re old-school like me, the Cruciferae), the Mustard family. It’s actually in the Papaveraceae (Poppy family).

At the time these pictures were taken in early June, these plants had already been blooming for two months. After I took these pictures, I removed all the plants (and there were many more than are visible in these photos!).

Part of coming to any new garden is learning the weeds. There are always new ones I’ve never encountered before, or that I recognize but am not familiar with. Learning what they are, how invasive or weedy they are, their lifecycle, how they propagate, and so on helps me prioritize their removal and monitor for their return.

For example, Chelidonium is a biennial. So pulling up visible plants before their seeds ripen and disperse kills this year’s generation and the generation two years from now. I might overlook next year’s generation this spring, but I’ll get them next year. The plants are shallowly rooted. By grabbing the plant at the base of the leaves, I can remove the whole thing easily, roots and all.

Chelidonium‘s seeds are dispersed by ants. They’re likely to show up next year close to where they were this year, but not necessarily in the same place. In addition, the soil probably has a reservoir of seeds from the years the garden was neglected. If I disturb the soil, or transplant plants from one part of the yard to another, they could show up in new places. By pulling the plants when they emerge in the spring, and keeping an eye out for their emergence in new places in the garden, I can easily control them. It will take a few years of vigilant weeding to eliminate them completely.

Note that, at a quick glance, this plant can be confused with the native* wildflower Stylophorum diphyllum, celandine-poppy. They’re very similar. Both are in the Papaveraceae, bloom in the spring with four-petaled yellow flowers, have lobed foliage and bright orange/yellow sap, and are about the same height. I find the seedpods the easiest way to distinguish them. The flowers of Stylophorum lack the prominent tall central pistil of Chelidonium, and the stamens form more of a “boss” around the center of the flower, not so obviously grouped in four clusters.

Stylophorum diphyllum, celandine-poppy, blooming and showing the distinctive, more poppy-like, ripening seedpods, in my urban backyard native plant garden, May 2013.

* Stylophorum isn’t native, or present, in New York. But it is native to eastern North America.

Related Content

Flickr photo sets:

References

- New York Flora Atlas (NYFA): ID 2059

- Invasive Plant Atlas of New England (IPANE): ID 108

- USDA PLANTS Database: Symbol CHMA2

- Wikipedia

An Elegy for Biophilia

I was moved to write this by a short missive from Reverend Billy:

When I go to pray, which is sometimes difficult being so without any god, I think of that time in my life, because the natural world was overwhelming the god that my family insisted was all-powerful and all-knowing. Creation was overwhelming the Creator and it came in the form of undulating prairie grasses.

I was raised in temperate and tropical suburbia. Even in those landscapes, the woods in the backyard, or the palmetto swamp at the end of the road or the canal, drew me to them. They were my expanse. Yet, compared to what existed before the forests were razed and the swamps drained, the landscapes of my childhood were impoverished.

The shifting baseline degrades further. More than half the world now lives in cities, with less ready access to nature than ever before in the history of our species. Biodiversity is an environmental justice issue.

I’ve chosen to live my adult live in a city. Even here, those childhood experiences guide me. I garden because it connects me to nature, it nourishes me. The beauty I invite is not of my making, but larger, deeper, and older than I can comprehend.

I believe it everyone’s right to have that connection for themselves. Not only a right, but necessary. Not only for our own health, but to have some hope for the future health of our planet.

That hope, however impoverished, is what keeps me going.

Pollinator Gardens, for Schools and Others

I got a query from a reader:

I’m working on a school garden project and we’d like to develop a pollinator garden in several raised beds. Can you recommend some native plants that we should have in our garden? Ideally we’d like to have some perennials and maybe a few anchor bushes. Are there any flowers that we might be able to start inside this spring then transplant? Also, because the students will be observing the pollinators, butterfly attracting plants are preferable to the teachers.

Whole books have been written on this topic, but here are some quick thoughts and references for further research.

Design Notes

- How much space is available for the garden? That will determine how many shrubs could be accommodated. Layout the woody plants first, then plan blocks of plants through the rest of the beds.

- Is it sunny? Shady? Mixed? Trees nearby? That will determine the types of plants that can be grown. Pollinators are more active in the sun, but you can still get plenty of action in shadier gardens. Just make the most of the sun and light you get throughout the day.

- How will it be watered while getting established? Who will water it? What happens during the summer while school is out? After the first year, once established with the right plant selections, watering needs should be minimal.

- Are the raised beds already established, or will they be filled with soil? Many “pollinator” plants fare languish in the rich soils prepared for the vegetables and edibles more typically grown in school gardens, and would prefer ordinary, even “poor,” soils.

- Plant multiples of the same plants in groups and patches, to make them easier for pollinators to find. It also provides a more continuous supply of nectar: if one flower or plant runs dry, another in the same patch can provide.

- See more about what to plant, below.

Plan for Pollinators

Pollinators visit flowers for two main reasons: nectar and pollen. We want to create habitat, not just a buffet. Plan to address the four basic needs: water, food, shelter, and a place to raise young. Host plants are just as important as flowers.

2-day old caterpillars of Battus philenor, pipevine wallowtail, on Aristolochia tomentosa, wooly dutchman’s pipevine, in my garden, June 2011

Even if we limit consideration to insect pollinators, there are many different kinds, including bees, wasps, flies, beetles, butterflies, and moths. Everyone wants butterflies, the divas of the garden. Some are squeamish about bees and wasps, but they really don’t bother people. Any flowers you grow will attract them, so they’re part of the garden already.

Multiple Pollinators on Pycnanthemum muticum, Clustered Mountain-Mint, in my garden, August 2011

Bees, of course, are all-around the most effective pollinators. But not just honeybees. There are scores of native bee species happy to take up residence in a garden.

Multiple nest entrances of Colletes thoracicus (Colletidae), Cellophane Bees, in my garden, May 2008

You can setup nesting boxes for native mason bees and carpenter bees. They’re fascinating to watch, and you can see how the nest tubes get occupied over time.

Bee Houses at the Greenbelt Native Plant Center, Staten Island, May 2010

Monarch butterflies are in steep decline and need our help. Milkweeds are their preferred host plants, so planting milkweeds is the best thing you can do to help monarchs. Several milkweed species are native to NYC. Many other pollinators are attracted to the flowers, as well.

NYC-local ecotype of Asclepias incarnata, Swamp Milkweed, in my garden, June 2008

Plant Native

- To get the greatest number and diversity of pollinators, choose plants that have clusters of many small flowers, such as plants in the Asteraceae (asters, daisies, sunflowers, goldenrods, etc) and Lamiaceae (mints) families.

- Include plants that bloom at different times of the year – especially very early and later in the year, when flowers are scarce – to provide a continuous supply of food for both adults and their young.

- Differences in flower size and structure affect which pollinators they can support.

- Insect-host plant associations can be very specific. Plants from different families support different species. So diversify the plant families you grow.

- Plant as many different species as your space can accommodate.

- Don’t forget to use the vertical space: include plants that grow taller and shorter.

- Plant in masses and blocks. Pollinators recognize they’re more likely to find pollen and nectar when several different plants, with many different flowers blooming at different stages, are available to choose from.

- The best plants for pollinators are native to the region, and – as much as possible – from local stock. This is true for both nectar and host plants. Prefer native species over non-native, straight species over cultivars, propagated from local populations over more distant ones.

I adapted this chart from published results of the Pollinator Plant Trial (PDF, 3 pp) at Penn State Southeast Agricultural Research and Extension Center (SEAREC)

My authority for “What’s native?” in my region is the NY Flora Atlas. You sometimes have to watch out for changes in nomenclature, but it’s an excellent resource. Resources for our adjacent states are the Native Plant Society of New Jersey and the Connecticut Botanical Society.

Your best bet for obtaining plants propagated from local stock is to work with nurseries based near you that specialize in native plants. In my area, for starting native plants from seed I recommend Toadshade Wildflower Farm located nearby in New Jersey. They have an astonishing range of native plants available, and seed for many of them. They’re passionate, experienced, and know their plants.

Related Content

FAQ: Where do you get your plants?

The 2014 NYCWW Pollinator Safari of my Gardens

Gardening with the Hymenoptera (and yet not), 2011-07-31

Gardening with the Lepidoptera, 2011-06-11

My blog posts on Butterflies (Lepidoptera), Bees and Wasps (Hymenoptera), Pollinators, Habitat, and Ecology

My Native Plants page

Retail sources for native plants

Me hosting the NYCWW Pollinator Week Safari in my Front Yard, June 2014. Photo: Alan Riback

Links

NY Flora Atlas

Native Plant Society of New Jersey: Plant Lists

Connecticut Botanical Society: Gardening with Native Plants

Biota of North America Program (BONAP): North America Plant Atlas (NAPA)

USDA PLANTS Database

Pollinator Partnership: Regional Planting Guide

Center for Biological Diversity: Native Pollinators

Xerces Society: Bring Bank the Pollinators

Wikipedia: Pollination Syndrome

Toadshade Wildflower Farm

NYC Wildflower Week

Research

Specialist Bees of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States

World Wetlands Day

Not only is it Imbolc, aka Groundhog Day (Flatbush Fluffy did NOT see his shadow today. You’re welcome.), it’s also World Wetlands Day. After seeing some of the photos shared by others on Twitter, I thought I would share my Flickr photo albums of some memorable wetlands I’ve had the privilege of visiting.

Cattus Island Park, Toms River, Ocean County, New Jersey

Cranberry Bog Preserve, Riverhead, Suffolk County, New York

The Hudson River, Riparius, Adirondacks, New York

Related Content

Links

Brooklyn Dirt, 2/16, Sycamore Bar and Flower Shop

I am honored and excited to be one of the inaugural speakers for a new event series: Brooklyn Dirt – Monthly Talks on Urban Garden and Farming. The topic of this first event is, appropriately, Dirt, aka Soil. If you have questions about soil, or dirt, let me know and Jay and I will try to cover the topic in our talk.

Prospect Farm and Sustainable Flatbush are proud to present Brooklyn Dirt: Monthly Talks on Urban Farming and Gardening.

Sycamore Bar and Flowershop

1118 Cortelyou Road

Brooklyn, NY, 11218

21 and over only

Directions: Q train to Cortelyou Road

Talk One: Dirt and Soil

Wednesday, February 16, 2011, 7-9:30pm

With Speakers Jay Smith and Chris Kreussling (AKA Flatbush Gardener)

$5 suggested donation. Proceeds benefit Prospect Farm and the Urban Gardens and Farms Initiative of Sustainable Flatbush.

Jay Smith is a lifelong environmentalist, member of several environmental organizations, member of the Park Slope Food Coop, completing a Certificate of Horticulture from BBG, deeply interested in Urban Agriculture and re-localization of food production in anticipation of food issues in the wake of the peak oil crisis.

Chris Kreussling (AKA Flatbush Gardener) is a garden coach with more than 30 years gardening experience in NYC. Chris is also the Directory of the Urban Gardens and Farms initiative of Sustainable Flatbush and a community member of the Healthy Soils, Healthy Communities advisory board, a project of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, and earned a BBG Certificate in Horticulture, 2009.

Sustainable Flatbush brings neighbors together to mobilize, educate, and advocate for sustainable living in their Brooklyn neighborhood and beyond.

Prospect Farm is a community group in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn that is working together to grow food in a formerly vacant lot, with the mission toward creating a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Farm that can serve our community. Prospect Farm is the community leader for the Kensington/Windsor Terrace neighborhood group for the Brooklyn Food Coalition.

The ground-breaking at Prospect Farm, initially called Windsor Farm, on March 31, 2010.

The facade of the newly opened Sycamore Bar and Flowershop on September 13, 2008.

[goo.gl]

Related Content

Windsor Farm Breaks Ground, 2010-03-31

Sycamore, September 15, 2008

Links

Facebook: Brooklyn Dirt: Monthly Talks on Urban Farming + Gardening

Event flyer

Prospect Farm

Urban Gardens and Farms Initiative, Sustainable Flatbush

Sycamore Bar and Flowershop

Dare we Dream of Spring? Happy Imbolc (Groundhog Day) 2011

Update 2011-02-02: Flatbush Fluffy didn’t see his shadow this morning. He did see his reflection in the sheet of ice that covers everything. Not sure what that means.

The snow in the backyard – undisturbed by shoveling, snowblowers, drifts, and pedestrian traffic, save for a few small, furry quadrupeds – is above my knees, about two feet. As I write this on the eve of the last day of January 2011, there is yet another Winter Storm Watch in effect, the billionth this Winter.

For the first day of February, the National Weather Service predicts snow, snow and sleet, freezing rain, sleet and snow, ice, freezing rain, snow and sleet, snow, then freezing rain, in that order. That’s just Tuesday. It continues into Wednesday, Groundhog Day, with much the same result. The sole consolation is that come Imbolc morn, Flatbush Fluffy, the resident Marmota monax, will not see his shadow. Dare we dream of Spring?

The groundhog, Marmota monax, also known as a woodchuck, groundhog, or whistlepig, is the largest species of marmot in the world.

Groundhog Day, celebrated on February 2, has its roots in an ancient Celtic celebration called Imbolog [Wikipedia: Imbolc]. The date is one of the four cross-quarter days of the year, the midpoints between the spring and fall equinoxes and the summer and winter solstice.

– NOBLE Web: Groundhog Day

The other cross-quarter days are Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain, associated with All Hallow’s eve, Halloween. The quarter days are the equinoxes and solstices, dates I also like to observe on this blog. The cross-quarter days fall between the quarter days. At the Spring equinox, day-length is at its mid-point, but the rate of change in day-length is near its peak. At Imbolc, day-length acceleration is near its peak; we are rushing toward Spring and Summer.

This is my fifth annual Groundhog Day post.This May will be the fifth anniversary of this blog. I am grateful for all the grace and privileges that have allowed me to continue doing this, and grateful for all my readers, friends, and community this endeavor has brought me over the years.

Regardless of the weather.

Related posts

Links

Wikipedia: Imbolc

11th Hour for Campus Road Garden

2010-02-23: Added a brief history of the Garden.

Last Fall, Brooklyn College announced plans to destroy the Campus Road Community Garden, located at the western end of Brooklyn College’s athletic fields since 1997, for a parking lot. This Wednesday, February 24, the Brooklyn Community Board 14 Committee on Education, Libraries & Cultural Affairs is having a public hearing:

When: Wednesday, February 24, 2010, 7 PM

Where: CB14 District Office, 810 E 16th Street, Brooklyn, NYAgenda:

1. Update on Brooklyn College Garden – Representatives of Brooklyn College and South Midwood Residence Association

2. Presentation on Brooklyn Public Library initiatives – Tambe Tysha-John, Cluster Leader, Brooklyn Public Library

3. Other businessIf you would like to speak during any of the public hearings or during the public portion of the board meeting, please call the CB14 District Office at 718-859-6357 to register for time. You may also register to speak on the evening of the meeting.

The “Brooklyn College Garden” is part of Brooklyn College’s greenwashing campaign. On February 3, they posted this announcement (since removed) on their Web site:

Brooklyn College announced today the creation of the Brooklyn College Garden that will serve as the basis for a broad spectrum of academic and sustainability initiatives for faculty and students. Members of the surrounding community will also be welcome to plant on individual plots, which will be assigned to them on a yearly base.

The garden, to be situated at the campus’s Avenue H entrance and bordering the college’s athletic field, is designed to be approximately 2,500 square feet.

which is where the Campus Road Garden, occupying more than twice the area, already exists.

View Brooklyn Community Gardens in a larger map

Brooklyn College’s unilateral announcement is disingenuous, at best. They omit any mention of their plans to destroy the Campus Road Garden, or the parking lot that will take its place. Such is the basis for their “sustainability initiatives.”

Not content with destroying a garden with decades of history in the community, they plan to pick at its bones for their private benefit:

Trees and bushes from a temporary community garden that made use of the area in previous years will be carefully replanted in front of the West Quad Center to create an inviting new garden. The college envisions the new green space as a “serenity garden” with comfortable seating for visitors to linger.

A garden that has been in place for 13 years is not a “temporary” garden.

Once again, the hearing is this Thursday, Wednesday, February 24, at 7pm, at the CB14 District Office at 810 E 16th Street.

[bk.ly]

A brief history

Provided by the Campus Road Garden:

- 1970s: Brooklyn College Organic Gardening Club starts a garden on a vacant college lot on Campus Road, sustained by community residents and students.

- 1980s: The City sells the lot at auction and evicts the gardeners. The developer defaults, and the lot remains vacant and overrun by weeds.

- 1990s: New Campus Road Garden Residents negotiate with the bank holding the property, and successfully recreate the garden. The bank again sells the lot and evicts the gardeners.

- 1997: Gardeners negotiate with Brooklyn College to relocate the garden to its current location. Then-President Vernon Lattin calls it “Brooklyn College’s gain.”

Related Content

Save the Campus Road Garden in Flatbush, 2009-10-07

South Midwood Garden Tour and Art Show, 2009-08-18

Other Gardens: South Midwood Garden Tour, 2006-07-30

Links

Stop the Demolition of the Campus Rd Garden, online petition

Education, Libraries & Cultural Affairs Committee, Community Board 14

Land of the Free, Home of the…Cars?, Dassa Gutwirth, Sustainable Flatbush, 2010-02-23 (Illustrated with my photos of Campus Road Garden)

BC issues plan for new community garden, stirring ire, Courier-Life, 2010-02-09

Saving the Campus Road Community Garden from Parking Lot Fate, 2009-10-19

Brooklyn College to pave over popular garden to expand track, Flatbush residents not pleased, Daily News, 2009-10-09